“In Sanatana Dharma, among all the spiritual traditions, Tantra is considered to be the most ancient, and among all the schools of Tantra, Samaya is the highest. The school of Samaya is profound in both its philosophy and practices, and it is this school that gave rise to the eternal knowledge of Sri Vidya.”

Swami Rama

Tantra is an ancient spiritual tradition common to Hinduism and Buddhism, and it contributed immensely to the ideology of other Asian belief systems. Teun Goudriaan describes Tantra as a “systematic quest for salvation or spiritual excellence by realizing and fostering the divine within one’s own body, one that is a simultaneous union of the masculine-feminine and spirit-matter, and has the ultimate goal of realizing the “primal blissful state of non-duality.” It can be described as a broad and diverse practice of the methodology of Shaktism.

Leora Lightwoman explains how Tantra evolved into its present-day form in an article titled “The history of Tantra”:

“Tantra is not a religion, although Tantric symbology and practices have emerged throughout history in all religions and cultures. Representations of the sacred union of the masculine and feminine principles and the non-duality of this “sacred inner marriage” can be found as far back as 2000 BC in the Indus Valley civilization and the old Egyptian kingdom. Tantric principles are inherent in mystical Judaism (Kabbalah), Christianity and Sufism. Chinese Taoism is another strand of Tantra.

The origin and history of Tantra are shrouded in mystery and continue to be the subject of frequent discourse among theologians. Many scholars believe that Tantra has its beginnings in the Indus Valley (current-day Pakistan and North Western parts of India) somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000 years ago when the Vedas were written. But Tantra did not come into common practice until the fourth century, at around the same time, Patanjali’s yoga philosophy began to take root and flourish.

The first Hindu and Buddhist Tantric texts can be traced back to 300 to 400 CE and were purposely obscure so that only initiates could understand them. Until this time, Tantric teachings were closely guarded and transmitted orally from master to disciple only after long periods of preparation and purification. Tantra reached the height of its popularity in the 11th and 12th centuries when it was practiced widely and openly in India.

Mathias Rose writes in The Origins of Tantra: ” The teachings that began to spread throughout India had a powerful attraction to a populace that was increasingly well off and had a robust middle class. The prosperous middle class was by and large left out of the caste conscious religions of Vedic origin and monastic-male Buddhism. Moreover, unlike the well-established and increasingly scholarly traditions, these teachings were vibrant, immediate and taught that enlightenment was available right now. in this life. No reincarnation is needed. The Divine was seen not as an abstract and distant deity or collection of deities, but an all-pervasive presence that each of us is not just a part of but- intriguingly the whole of. “

Renowned yoga scholar Georg Feuerstein believes that Tantra came about as a “response to a period of spiritual decline, also known asKali Yuga, or the Dark Age, that is still in progress today.” He suggests that powerful measures were needed to counteract the many obstacles (such as greed, dishonesty, physical and emotional illness, attachment to worldly things, and complacency) to spiritual liberation. He writes that “Tantra’s comprehensive array of practices, which include asana and pranayama as well as mantra(chanting), pujas (deity worship), kriyas (cleansing practices), mudras (hand gestures) and mandalas andyantras (circular or geometric patterns used to develop concentration), offered just that. Also, Tantra wasn’t exclusively practiced by the noble Brahmin class. It gained power and momentum by being available to all types of people—men and women, Brahmins and laypeople, could all be initiated.”

Until even a hundred years ago, not much was known to the world about the practices of Tantra as most of the knowledge was passed down in India through the oral tradition from teacher to an initiated disciple. Significant debate surrounds the complex, and at times, a controversial body of knowledge that constitutes Tantra. In the Nath tradition, the origin of Tantra is ascribed to Dattatreya, who is said to be the author of Jivanmukta Gita (Song of the liberated soul). Matsyendranath is said to be the author of the Kaulajnana Nirnaya, a 9th-century book that deals with several mystical subjects.

“There are widely different Tantric texts,” says meditation teacher Sally Kempton, “and different philosophical positions taken by practitioners of Tantra. However, one core aspect of Tantric philosophy remains consistent: That aspect is nondualism or the idea that one’s true essence (alternatively known as the transcendental Self, pure awareness, or the Divine) exists in every particle of the universe. In the nondualist belief system, there is no separation between the material world and the spiritual realm. Although, as humans, we perceive duality all around us—good and bad, male and female, hot and cold—these are illusions created by the ego when, in fact, all opposites are contained in the same universal consciousness. For practitioners of Tantra, that means that everything you do and all that you sense, ranging from pain to pleasure and anything in between, is really a manifestation of the Divine and can be a means to bring you closer to your own divinity.”

In Hindu dharma, enlightenment is often seen as a process that takes several lifetimes. The Tantra philosophy, on the contrary, suggests that enlightenment is possible in one lifetime. Hinduism holds three concepts at the very core of its essence: Brahman (the Absolute), Vedas (sacred knowledge) and Moksha (liberation from the never-ending cycle of death and rebirth). Brahman is the nature of truth, wisdom and infinity, according to the Taittariya Upanishad (“satyam jnanam anantam brahman“). It is above and beyond the human construct of time, space and matter. Brahman is derived from “brh,” meaning “that which grows (brhati) or that which causes growth (brhmayati).” Brahman is often loosely translated as God, but a more profound study suggests a definite conception of the Absolute – it transcends all dualities and classifications. The Brahman is the Absolute Truth (param satya) and the omnipotent and animating life-principle (chit-atman).

The ultimate aim of a Hindu is to become one with the Brahman.

The paths to becoming one with the Brahman are many – knowledge, devotion, good deeds and meditation are of primary importance, but there are no distinctions made between these paths as they are bound to intersect and work in combination in the due process of living.

The first path to liberation is knowledge, which is contained in the Vedas – the oldest Hindu scriptures that contain information on all aspects of life. The word Veda comes from “vid,” meaning “to know,” and it serves to manifest the language of Brahman to humanity. Tradition indicates that the Vedas were not composed by humans but were revealed to enlightened rishis or seers and passed down from generation to generation through oral tradition.

The Vedic knowledge is said to be “Shruti” – one which has been heard (consisting of revelations) is the unquestionable truth and can never change. Other forms of knowledge are “Smrithi” – those which are remembered (an outcome of the intellect) and can change over time.

The Vedas are not a mere collection of scriptures but a living, ever-expanding, dynamic communication between the Brahman and humanity using the subtle laws that govern the universe – sound, form and color. Humans can utilize the knowledge contained in the Vedas to lead them to moksha, which is liberation from suffering and the endless cycle of death and rebirth. It is the return to Brahman – the realization of the Self as the Absolute.

Hindu dharma clearly states that liberation is not exclusively promised to one who embraces sanyasa. It is equally possible for a householder, who aspires for material prosperity and enjoys a sensory life, to seek moksha. In both cases, the pursuit of knowledge is the starting point of the journey. A sanyasi should pursue methods that would lead him to understand his Self. In contrast, a householder should pursue learning, which becomes the basis of dharma (moral duties), artha (wealth creation) and kama (sensual enjoyment).

While a sanyasi can seek his Brahma vidya through renunciation, asceticism and meditation, a householder can begin his journey into the deepest point of his being through a study of the Tantra and Sri Vidya.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad considered the crown jewel among all the Upanishads, carries the famous statement “Aham Brahmasmi (I am Brahman or Divine Consciousness).” This pithy declaration encapsulates the entire philosophy of Sanatana Dharma, the Hindu faith. This one short statement is sufficient to disprove all the misconceptions about Hinduism, and the pantheon of gods worshiped within its broad framework. Hindu dharma’s basic premise is that only one Supreme Being is given different names, forms, and assigned specific qualities. This manifestation as various divine bodies helps establish a speedier connection between humans and the Divine as it reduces the Supreme Being to a more tangible, approachable and relatable entity. Throughout the history of this ancient religion, there have been many sects that have formed as an outcome of devotion to one particular form or one specific philosophy. In general, Hinduism can be categorized into four major denominations:

- Vaishnavism – worship of Vishnu

- Shaivism – worship of Shiva

- Shaktism – worship of Mother Goddess or Shakti

- Smarthaism – belief in the essential oneness of all gods; offers a personal choice to the worshipper to determine his (own) God

All the four denominations are united in the common purpose: to further the soul’s unfoldment to its divine destiny. Several concepts, such as accepting the Vedas as the ultimate authority, belief in the doctrines of karma, reincarnation, etc., are common to all. They differ primarily in terms of the God worshipped by the particular sect as the Supreme Being and the traditions that are followed in offering worship to that God. Each of these sects has its own temples, pilgrimage centers, sacred literature and guru lineages.

Shaktas, as the practitioners of Shaktism are commonly known, conceive the Goddess as a representation of the primordial energy and source of the cosmos. Shaktism is based on the Vedas, Upanishads and Puranas that speak about Shaktism’s prevalence during different historical periods, beginning with early Vedic times, waxing and waning in its influence, gaining maximum prominence during the Epic period. Shaktism is believed to have evolved out of a rebellion against the power that Brahmins exercised in society and a desire to return to the archetypal Mother Goddess concept that existed in prehistoric times. The most essential propagators of Shaktism have been the practitioners of Advaita Vedanta, including Adi Shankaracharya.

In Shaktism, the world is not approached as Maya or illusion. It is perceived as real with all its aspects (even the ugly, gross and unholy) as Divine. Shakti evolves into 36 tattvas or elements to create the universe. Therefore, the universe and everything it contains is a mere manifestation of Shakti. The Brihadaranyanka Upanishad includes a reference to a spider spinning its web from its mouth and moving through its own creation of concentric circles, putting forth new threads and pulling back others while controlling all of its creation from one single point. This image conveys the essentially Vedic thought that all existence arises out of and eventually returns to one single principle.

The human body is held sacred as it is the temple of our spiritual unfoldment.

Shaktism can be classified into Srikula, or family of Lakshmi and Kalikula or the family of Kali. In both aspects, Shakti is worshipped by mantras, mudras and yantras.

One of Shaktism’s most well-known sub-traditions is Tantra, which refers to techniques, practices, and rituals and involves mantra, mudra and yantra. Swami Amrithananda Saraswathi describes it as a technique of worship that removes limits to what you can know and do.

The Vedic knowledge “Shruti” is considered to be the highest form of knowledge. Shruti texts include two types of scriptures called Agama and Nigama. Agama is derived from the verb root “gama,” which means “to go” and the preposition “a,” which means “toward” and refers to scriptures as “that which have come down.” Agama can therefore be understood as precepts and doctrines that have come down as tradition. Nigama, on the other hand, can be understood as a passage from the Vedas, a statement in the Vedic passage or sacred tradition or Vedic literature in general.

There are three types of Agama scriptures:

- Vaishnava Agama – which is focused on Vishnu as the Supreme Being

- Shaiva Agama – which sees Shiva as the Supreme Being

- Shakta Agama – which regards Shakti as the Supreme Being

Tantra is seen as a sub-system of Shakta Agama. There is speculation even among scholars about whether Tantra is a Vedic tradition. Many authors claim that the Vedic tradition is an Aryan one, while the Tantric practice is Dravidian in origin. Pandit Vishwa, the founder of Vishwa Yoga, writes in his article on the difference between Vedas and Tantra: “In reality, the Vedic and tantric traditions are both parts of one great system even if there are a few differences in their approaches. The Vedic tradition is an earlier form of the tantric tradition. For example, the Atharva Veda is technically a tantric text. Therefore it will be correct to assume that both Tantra and Vedas are important systems of Indian philosophy. Tantra glorifies individual power and practices, while Vedas emphasize collective power and rituals. However, both share the common goal of self-realization.”

Tantra represents the practical aspect of Vedic traditions. It is called a “Sadhana-shastra,” which means that it is practice-oriented as opposed to other traditions that are philosophy-oriented. Tantra accepts that the body exists with all its energies, good and evil; in the same way, the world exists with all its energies, good and bad. In this sense, Tantra is seen as a body-affirming and world-affirming spiritual tradition. This is in direct contrast to the classical view, which insists on renouncing worldly life to attain liberation. This aspect of Tantra allows householders to aspire for spiritual liberation while enjoying the sensory pleasures of life.

Leora Lightworker writes that “Tantra has been and still is practiced in three primary forms: the monastic tradition, the householder tradition and by wandering yogis. Whereas Hinduism had many rules and laws, including strict caste divisions, Tantra was totally non-denominational and could be practiced by anyone, even within daily life.

Thus meditations on weaving, for example, could be practiced by weavers, as they contemplated the interwoven and undifferentiated nature of existence, whereas meditations on eating, drinking and lovemaking could be practiced by kings and queens.”

Tantra rests on three pillars:

- The methodology, skills and techniques

- The mantra, which on the gross level are unique sounds, but on a deeper level, they are a vehicle of consciousness. It is said that the world materialized and came into shape through sound, and therefore, sound acts as a link between the form and the formless.

- The yantra is a geometric diagram used for rituals or worship in Tantra practice, and the yantra becomes the center of the universe symbolically.

While Tantra, mantra and yantra are the three pillars of the Tantra system, yoga is the practical application of Tantra.

Tantric Master Shri Aghorinath Ji says: “Tantra is different from other traditions because it takes the whole person with all his/her worldly desires into account. Other spiritual traditions ordinarily teach that desire for material pleasures and spiritual aspirations are mutually exclusive, setting the stage for an endless internal struggle. Although most people are drawn into spiritual beliefs and practices, they have a natural urge to fulfill their desires. With no way to reconcile these two impulses, they fall prey to guilt and self-condemnation or become hypocritical. Tantra offers an alternative path.

“Tantra is an ancient yet vibrant spiritual science. It is unique in that it takes the whole person into account. Other spiritual traditions ordinarily teach that desire for worldly pleasures, and spiritual aspirations are mutually exclusive, setting the stage for an endless internal struggle. Although most people are drawn to spiritual beliefs and practices, they have a natural urge to fulfill their worldly desires. With no way to reconcile these two impulses, they fall prey to guilt and self-condemnation, or they become hypocritical, or both. The tantric approach to life avoids this pitfall.”

There could not be a better way to explain Tantra than this, as Pandit Rajmani Tigunait writes in the Living Science of Tantra. He describes possibly one of the most complex, grossly misunderstood and misinterpreted terms of ancient Hindu traditions in simple terms. The word Tantra is sadly synonymous in the West with erotic sexual practices, while in India, it is most often labeled as occult and dark – sometimes known as “the left-hand path.” Tantra suffers from its association with macabre Aghori traditions (eating/drinking from a skull, crematorium rituals, intoxication, sexual orgies). This is so far from the truth that the Tantra tradition expounds.

The word itself is derived from tan (Sanskrit for “to expand” or “to spread”) and tra (meaning instrument). Tantra literally means a mechanism to expand consciousness. Some Vedic scholars also interpret that the word means “to weave,” seeing the universe as a web in which everything is interconnected. Other scholars understand the word Tantra to be a “sly pun.” Mathias Rose writes that to understand this pun, one must first understand the word sutra. At that time, a core part of the prevailing religions (Buddhism, Jainism and Vedic traditions) consisted of sutras – essential collections of compact principles. Etymologically a sutra literally means ‘thread’; therefore, a sutra is a thread of thought or a particular line of thinking. If a sutra is ‘a single thread of thinking’, Tantra is the whole system of thought. Therefore, the etymological essence of Tantra can be seen as the “next generation” advance of thinking about the sutras. Initially, sutras were a collection of aphorisms, while tantras were holistic spiritual teachings that could only be transmitted directly from teacher to student.

Antoaneta Gotea writes in Hridaya Yoga that Tantra philosophy can best be expressed as “nothing exists that is not divine.”

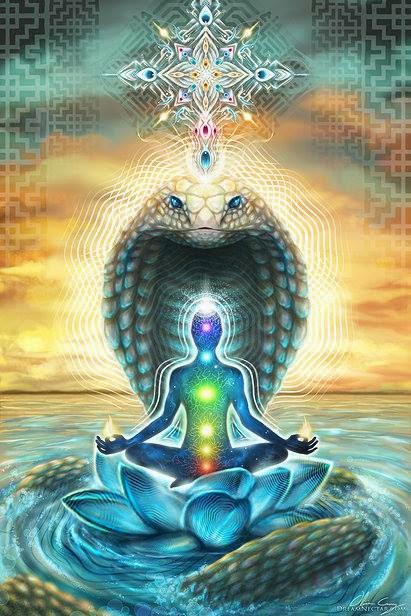

In Tantric tradition, the universe is alive and brimming with joy and bliss. All manifestations are seen as an interplay between Shiva, who symbolizes pure consciousness, the unchanging, unlimited masculine principle and Shakti, representing the activating energy, the provider and the Mother, the feminine principle. Shiva and Shakti are merely manifestations of the Brahman, but only when Shiva and Shakti combine that creation can occur.

Tantra actually seeks to dissolve the separateness of the mundane from the spiritual. Every aspect of life is seen as a tool for spiritual growth. The body is seen as a living temple, and all of its energies – positive or otherwise – are considered tools for spiritual progress and transformation. Tantra is profoundly devotional and highly ritualistic, but these rituals are a means to see and experience life and its energies as divine manifestations. To embody the essence of Tantra that “nothing exists that is not divine,” it is said that it is equal to Self-realisation.

Tantra is generally classified into three major schools, although there are many subdivisions within these:

- Kaula

- Mishra

- Samaya

Kaula Tantra’s practice is focused on external rituals and processes. Mishra Tantra advocates a mixture of external rites and techniques combined with internal practices. Samaya Tantra describes an entirely internal process, a purely yogic practice with no use for external rituals. Kaula Tantra is seen as the lower form of practice, and Samaya Tantra the highest in the hierarchy of tantric practices.

The word kaula comes from the term “kula,” meaning “family.” This means two things: One, that this path can be practiced by those embracing family life, and two, that everything in this universe is a part of one large family, much like in the concept of Vasudaiva Kutumbakam as seen in latter-day Vedic texts and philosophies.

Kaula practices consist mainly of worshipping external objects by way of rituals. These rituals include the use of idols, mandala, yantra, minerals, herbs and so on. The emphasis in this path is on devotion and faith, which is expressed by way of external worship. Many scholars point out that Kaula’s practices are focused on the lowest three chakras, namely Muladhara, Swadisthana and Manipura.

Within the Kaula Tantra, we see two types of paths – the left-handed path and the right-handed path – based on the practices that are followed. The left-hand path is known as Vamachara Marga, a non-conformist, non-orthodox path with no distinction between good and evil, pure and impure, clean and unclean. Sometimes it is seen as a path that uses means which go against the norms and ethics laid down by society.

The Panchamakara ritual that some Tantra practitioners follow entails the use of taboo substances such as wine, meat, fish and sexual union. The Dakshina Marga (right-handed path) follows practices that are more conformist, focusing on mantra, yantra and well-defined processes for spiritual growth. There is no wrong path in Tantra but, in modern times, the Kaula Marga has been at the receiving end of a great deal of flak as it is grossly misunderstood and misrepresented, especially by Western theologians who do not quite understand the subtleties involved in the comprehension of ancient Hindu Vedic texts.

Mishra Tantra is a school where both external and internal practices are combined – worship is done using both rituals and mental practices. While the rituals continue to include mandala, yantra and herbs, here it is combined with asana, pranayama, dharana and dhyana. The focus here is mainly on awakening the Anahata Chakra, and the eventual desire is to remove dependence on all external objects of worship and to channel it inwards completely.

Samaya is considered the loftiest school of Tantra as we now move from the gross aspects of worship to the most subtle. Here, the practices are purely internal with absolutely no external objects or rituals. Yogic practices such as asana, pranayama, dhyana and samadhi are emphasized, and the human body is seen as a yantra and worshipped accordingly. The Sahasrara chakra is the main object of focus in this school of Tantra.

As humans, we are continually evolving, learning and changing with every life experience. Every life experience can either be an external one or an internal one. Based on how the energies move in any specific experience, there is a corresponding change in the state of awareness. An experience that occurs due to the sense organs is an example of outward moving energy. For example, our desire to enjoy food or drink leads us to seek fulfillment of this desire through external sources. Therefore, we can see this energy movement as an outward and downward one since it further entangles us in the snare of Maya or illusion.

On the other hand, when we seek fulfillment from within by involving ourselves in practices such as chanting, meditation, mindfulness or prayer, we can see that the energy movement is inward and upward. We are now slowly disentangling ourselves from the veil of ignorance as we move towards spiritual growth and development.

Based on this movement of energy (outward and downward or inward and upward), tantra texts define two paths that any individual may take in his life journey:

Pravritti Marga (The Natural Path)

This is the path of the outward movement of energy that leads us to the world of activity, seeking enjoyment and fulfillment, an extroverted nature with normal and natural social interactions. People on this path live as householders, fulfilling their obligations and responsibilities with perhaps an inkling of the understanding that all they are seeking is transient and impermanent.

Nivritti Marga (The Source Path)

This is the path of inward movement of energy that a person who wishes to become one with the source embraces. It is the path of the renunciate or the hermit, and yet, it does not mean that one has to withdraw from society or community. It only requires developing a gradual disinterest in all material and worldly pleasures.

In Tantra, Shakti (the Goddess) is secret and subtle. She reveals herself to the seeker only after years of intense devotion and sadhana. Shakti, therefore, compromises the inner guiding light, the knowledge and its comprehension. Hence, Shakti is vidya. “In Tantra, the world is not something to escape from or overcome, but rather, even the mundane or seemingly negative events in day-to-day life are actually beautiful and auspicious,” says Pure Yoga founder Rod Stryker, a teacher in the Tantra tradition of Sri Vidya. “Rather than looking for samadhi, or liberation from the world, Tantra teaches that liberation is possible in the world by emphasizing personal experimentation and experience as a way to move forward on the path to self-realization.’’

Renowned Tantra Master Shri Aghorinath Ji writes: “Tantra also can be understood to mean “to weave, to expand, and to spread,” and according to tantric masters, the fabric of life can provide true and everlasting fulfillment only when all the threads are woven according to the pattern designated by nature. When we are born, life naturally forms itself around that pattern. But as we grow, our ignorance, desire, attachment, fear and false images of others and ourselves tangle and tear the threads, disfiguring the fabric. Tantra sadhana, or practice, reweaves the fabric and restores the original pattern. This path is systematic and comprehensive. The profound science and practices pertaining to hatha yoga, pranayama, mudras, rituals, kundalini yoga, nada yoga, mantra, mandala, visualization of deities, and alchemy, Ayurveda, astrology, and hundreds of esoteric practices for generating worldly and spiritual prosperity blend perfectly in the tantric disciplines.”

426 total views, 1 views today